The book Why Me? continues to be relevant as we struggle through these challenging times. Why does God test humanity, and why do innocent people have to suffer in the process?

The following is an excerpt from the last chapter of my book. It addresses the question of why innocent people suffer. Next week I will address the question of how and why God sends tests to humanity as a whole.

There is only one question that is more difficult to answer than the one we began with [why do bad things happen to us], and that is the question of the suffering of innocent people—especially children. This is a question that has shaped the teachings of all the world’s philosophies and religions, and yet the answers have left the majority of humanity in despair.

Previous religious traditions have told us that all people suffer because we are evil at heart and deserve to suffer. Western religions say that even children deserve to suffer because of original sin, while Eastern traditions say we are born with a “karmic debt” from our “past lives” that must be redeemed through suffering.

I would like to propose a different, and, I hope, encouraging alternative to these explanations—one that reinforces both the Justice of God and the essential goodness of the human spirit.

Now, it is helpful to break the question into two parts. How can God allow innocent children to suffer and call Himself just? And why does God allow innocent children to suffer if He is capable of stopping it?

The first question is actually fairly easy to answer if you believe in an afterlife. Many religious traditions speak of a spiritual recompense for innocent victims of accidents or oppression. The Bahá’í Writings offer this example:

This question is much harder.

I start by restating the point I made at the beginning. The purpose of life is to develop virtues. Most virtues can be defined in terms of our relationships to others. Compassion, generosity, service—these virtues cannot exist unless someone else is in need. The more severe the need, the more it cries out to be aided by virtue.

Just as it is impossible for us to develop forgiveness without someone doing us wrong, how could we possibly develop a passion for justice and a spirit of compassion unless we could look around and see the need for these virtues in the world?

So what I am proposing is that the universality of the grief, the intensity of the righteous anger, the hunger for justice, and the outpouring of compassion and empathy that arise when innocent people suffer, are themselves the very reason for the suffering. These are noble virtues. The world is in need of them, and they cannot be called into existence in any other way.

Consider the option of allowing only the guilty to suffer. Would we bother to feel compassion? Would we work fervently to end their pain? Would the atmosphere of love and unity within society increase with the knowledge that only the guilty need to worry about unexpected difficulties? Ha.

Consider the caste system of India. In a society in which all suffering is perceived as the just consequence of past sins, the poor make little effort to improve their “preordained” situation. Likewise, the rich complacently use and abuse people who they believe “deserve” to be treated like dogs.

Of course, this same perspective creeps into attitudes towards the poor in the West as well. If we believed that the poor or homeless were innocent, how could we stand to see their poverty and suffering?

And so it is important that we each have the opportunity to witness the suffering of someone we consider too good or innocent to deserve whatever pain and sadness they are experiencing. It forces us to explore the corners of our own humanity—the depth of our compassion, the heights of our righteous indignation, the breadth of our generosity and the length of our service. It connects us to others—both the sufferers and the other observers—and reinforces our oneness.

These are important lessons. They are the gifts of the innocent, and the givers are recompensed one-hundred fold by the One Giver who holds us all in the hollow of His hand.

This brings me to the last kind of test—the one that is intended not just for an individual, but for humanity as a whole.

***

I will tackle THAT question another time.

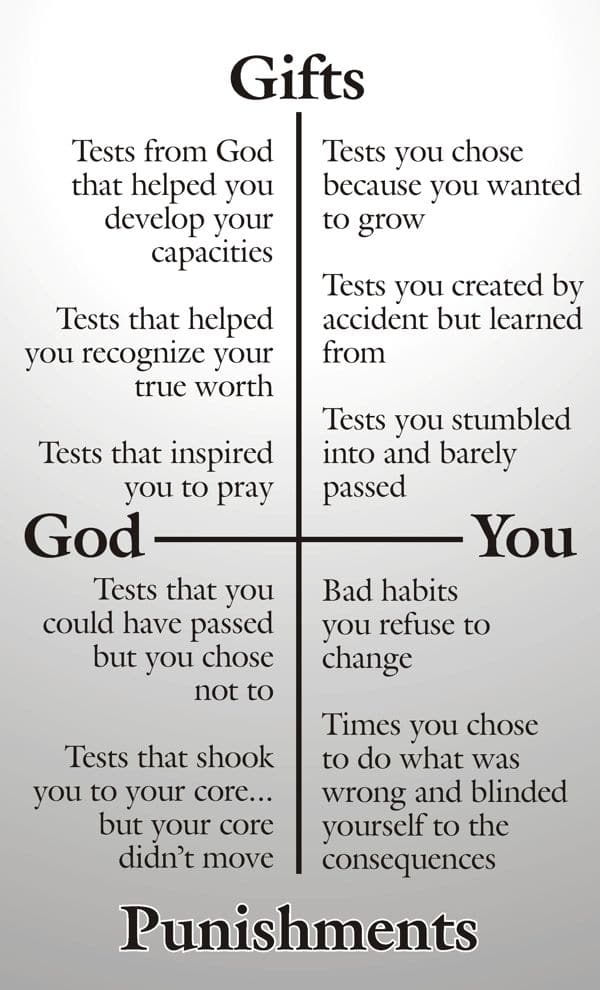

In the mean time, here is a reminder of the four kinds of tests that I told you about last year. It is from an earlier chapter.